Laws of Form - The Challenge

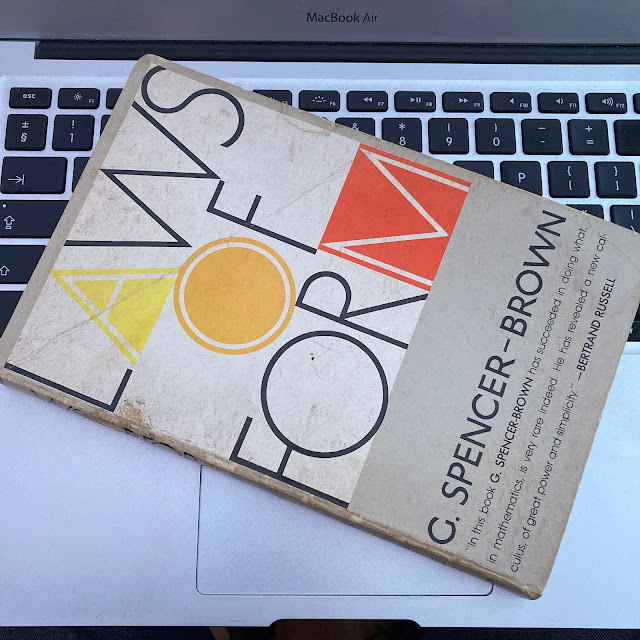

Way back in the early 1980s, I came across a review of a book in a computer magazine - I forget which one - which was rather intriguing: 'Laws of Form' by G. Spencer-Brown, originally published in 1969. The review was sufficiently tantalising to compel me to order it via some abstruse route from the United States, as it was at that time out of print in the UK. Why the magazine had chosen to review such an old book that was so difficult to get hold of - no Amazon, no online anything - I don't know; but I ordered it anyway. Weeks went by and eventually the book turned up. To say I was mystified by its contents is perhaps understating the fact. Not only was the subject under discussion staggeringly abstruse, but the language the book was written in seemed simultaneously straightforward and totally impenetrable. I figured that the pull-quote used on the front cover as a blurb probably should have given me a clue that I was going to be out of my depth here. '"In this book G. Spencer-Brown has succeeded in doing what, in mathematics, is very rare indeed. He has revealed a new calculus, of great power and simplicity." - Bertrand Russell.' Warning signs aplenty, methinks. So the book joined the rest of my library and apart from the occasional, quizzical flick through, there it remained.

Many years later, I lent it to an acquaintance who possessed a PhD in mathematics and asked if he could make sense of it for me. Several weeks later, the book was returned by its temporary custodian with a bemused and rather wry look. No comment and no dice. The reason I'm relating this is that the man who developed the Zettelkasten method I've previously written about; Niklas Luhmann, refers to the book and Spencer-Brown in his writing, which has further piqued my interest, if not my understanding of its subject, in the book. Following some judicious Googling and hitting the appropriate WikiPedia pages, I discovered that Laws of Form was written in E-Prime, denoted by the symbols E' or É; a form of English that to quote WikiPedia, '...excludes all forms of the verb to be, including all conjugations, contractions and archaic forms.'

This form of English was apparently developed to 'clarify thinking and encourage writing', but I rather think the jury's out on that one, with as many detractors as adherents in evidence. My tendency is to support the detractors, but I could be wrong! It just seems to me to be an impoverished mode of language that gets in the way of the message intended; a bit counter-intuitive in my book. I don't think that was necessarily the sum-total of my complete bafflement by the book, but it certainly didn't help.

The subsequent articles I read about it, in rather more everyday english, certainly helped to show me some of the logic of the thing. The hard work starts now, I guess. Understanding something totally new is always a good, if not an easy thing to do, but I'll give it a go. At least having it rendered into a language I can relate to has taken me back to the time of that review; thirty-seven years on, I think again that there just might be something significant in this stuff.

Comments

Post a Comment