A Tale of Two Industries

|

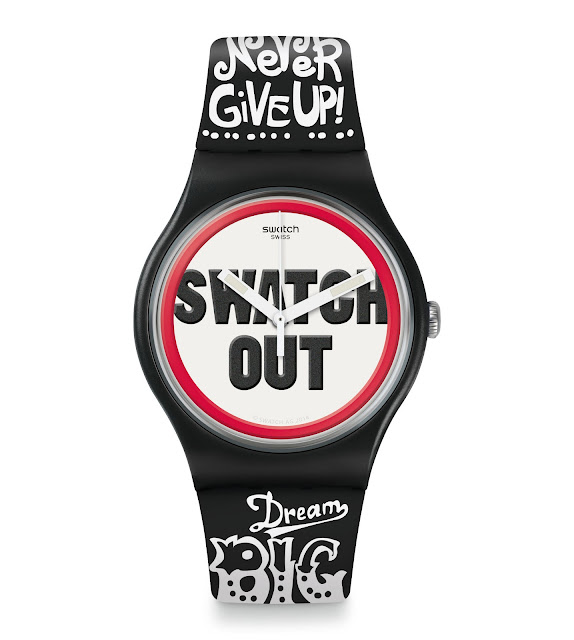

| Image - ©Swatch |

Sometimes good ideas and the products that follow from them simply arrive at the wrong moment in time, others quite the opposite. Two such ideas in quite different spheres, both emerged out of crises in their parent markets in an attempt to rescue their respective businesses.

The first of these critical responses was that of Swatch, the Swiss watch company founded in 1983 by Nicolas Hayek. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s the watch market was moving away from the traditional mechanical watch toward the complete adoption, or so it seemed at the time, of the cheaper and more accurate quartz watches issuing from Japan. By the early '80's, the Swiss watch industry was in a state of panic as its market share plummeted. Hayek founded Swatch to address this imbalance; the name is a contraction of 'Second Watch', as the company envisaged that their customer base would adopt these cheaper, electronic watches as daily wearers, alongside their more expensive mechanical pieces.

What happened next was rather surprising. Swatch produced designs in relatively 'limited' editions, seasonally; so each year would see several different design themes, most of which would not be made again. This and the fact that they were made by a Swiss company, along with the 'high-end' design quality, made them highly fashionable and to large numbers of followers, desirable and collectible. As the old century became the current one, there was a resurgence in interest in mechanical watches. At the highest bespoke end of watchmaking, not much had changed, but at the more affordable end of the market, the downturn was reversed and has led, helped by both the influence and the cashflow of Swatch, to the present day's buoyant watch market, where quartz Seiko divers' watches sit happily alongside Rolexes and Patek Philippe's in the greater watch pantheon. The idea of competing for the survival of the industry was actually instrumental in bringing the original industry back to life, seeing many long-since defunct brands and manufactures making a comeback.

|

| Canon IX7 APS Camera |

For similar technological reasons, the mid 1990s saw a like crisis in the world of photography. The advent of affordable digital photography around the middle of the decade throwing the analogue world of film and film processing into a tailspin. 1994 saw the introduction of the first genuinely commercial digital camera: the Apple QuickTake 100. There were a couple of others out there prior to the QuickTake, but it was the first onto the mass market.

Frankly, the performance of the thing in terms of image quality was pretty dire. It only took and stored pictures at VGA (640x480 pixels) resolution, so they were only usable on-screen at their original size; printing them was a joke. Apple discontinued the product line on the return of Steve Jobs to the company and it would take the eventual introduction of the iPhone to see Apple's return to photography.

The still film industry could see the writing on the wall however, and whilst it could more than hold its own on quality compared to digital, the lowly digital had a trick up its sleeve - metadata. Each digital image could store camera, exposure, date and a host of other details as part of the file. Today, the metadata is more extensive than ever, including geo-tagging and a whole host of customisable information, image file formats needing no structural alteration to include new and different types of data. Digital's ease of use plus this added informational bonus was giving the digital camera an edge over film, despite the poor image quality, an issue that was nevertheless improving rapidly with each iteration of the platform's development.

The still film industry tried to stem the tide of digitisation by introducing a completely new film format in 1996: the Advanced Photo System or APS for short. As clever as it appeared timely, this system introduced a number of innovations. Firstly, and harking back to the days of Kodak's early history ('...you just push the button, we do the rest...') it saw the introduction of a format that tied the user into the processing house. The film automatically wound itself back into its sealed cassette, ready for processing; the completed roll being sent away and the prints returned from the processing house complete with the negative, still as a roll, wound back into the cassette ready for sending off for reprints if necessary.

The really innovative side to this film was the inclusion of data generated by the camera. Whilst data backs had been around in the film industry for decades, they worked by marking the film in some way, so that when processed, the information came out on the borders of the negative - fixed and immutable. The clever bit with APS (at least in more expensive cameras using the system) was a transparent magnetic layer on the film which could store digital data: metadata similar to the digital camera format.

While film's image quality remained superior to digital, I suppose it was reasoned; there would no real incentive for people to swap to digital. What they didn't foresee, though, was the extremely rapid improvement in the quality of digital imaging. This coupled with what should have been glaringly obvious: the format just didn't suit professional photographers. The negative format was too small at just over half-frame area compared to 35mm and the locked in cassette system, whilst it could have been subverted for DIY processing, was just extra faff; along with the smaller negative size it simply made the format unattractive. The system was discontinued in January 2004. By then, digital was just too good for it to compete.

The entire still film industry nearly followed it into the grave, but sufficiently robust pockets of interest survived around the world, principally in the US and eastern Europe, to ensure its survival in a niche market. It has now mutated into a boutique enthusiasts' industry and many professional commercial and art photographers now use film again, alongside today's remarkable digital equipment, often shooting on film and then scanning and digitally printing images. Thus, two analogue industries have managed to survive the digital onslaught despite the odds and both look rudely healthy as we enter the third decade of the 21st century. May it continue.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete